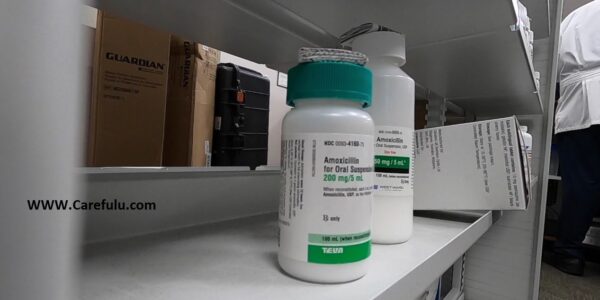

The USA is short on amoxicillin and Tamiflu amid a surge of RSV and flu

The United States, the world’s richest country and its most important developer of pharmaceuticals is not about to run out of prescription drugs. And still does it all the time.

In the past few weeks, shortages of amoxicillin and Tamiflu have been reported amid an increase in respiratory infections. Young patients with asthma who are infected with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) may need albuterol to relieve shortness of breath, but that drug has been in short supply for months.

Shortages of drugs to treat all types of conditions are occurring across the health system. Adderall has an ongoing shortage. In recent years there have been shortages of saline, morphine, and cancer drugs. When Covid-19 reached the United States two years ago, the country was already short of essential drugs for people put on ventilators. And when I learned two months ago about the shortage of Pitocin, the drug used to control bleeding from postpartum hemorrhage, Baylor College of Medicine OB-GYN Mark Turrentine told me that this localized Pitocin shortage wasn’t something that happened recently, but the last four or has occurred repeatedly in five years.

According to a 2022 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, the number of ongoing drug shortages is increasing and becoming more chronic. According to a report by the Food and Drug Administration, the main reason for that problem is the economics of the pharmaceutical market.

The causes of shortages are usually consistent regardless of the drug: either shortages of raw materials or problems at the factory where the drug is manufactured. Drug shortages that patients can pick up at pharmacies often make the most headlines, but most of the drugs that end up in short supply are generic, injectable drugs that are used in hospitals: typically, there are only one or two suppliers of these drugs. So if a company has problems at its factory, there is no easy way to increase production to make up for the shortfall. And they’re usually cheap, which means the companies that make them don’t have a strong economic incentive to produce any extra supplies.

We have not invested in building the capacity our country needs. It is expensive. If you’re going to sell something for a dollar a vial, there’s no incentive to invest, said Erin Fox, a pharmacist at the University of Utah who has researched drug shortages. It makes a lot of sense when you think about it from their perspective. But when you think about it from the hospital’s perspective, it’s very depressing.

Some of these deficiencies directly lead to patient death. An Associated Press report in 2011 linked drug shortages to at least 15 deaths in the previous 15 months. A recent study, after a year-long shortage of drugs used to treat septic shock, found higher mortality rates for patients relying on an alternative. Even if deaths are low, drug shortages can meaningfully change the care that patients receive, for example, if a pregnant person undergoes a cesarean delivery, she has a higher risk of complications and a longer recovery time because a drug that can induce labor earlier is a drug that can induce labor earlier. outside stock

Experts have ideas on how to make pharmaceutical supply chains more resilient. But they need federal government action. Until that happens, there is little reason to believe that the pace and duration of America’s drug shortages will slow.

Why drug shortages occur and sometimes their fatal consequences

Formulating prescription drugs is complicated. A company must first acquire the necessary components, sometimes from suppliers around the world. The producer must take that raw material and then manufacture the drug, in a factory capable of performing a technologically sophisticated manufacturing process, in the most cost-effective fashion, while also meeting FDA safety and quality requirements.

Check out this graphic from the National Academies report. Each drug on the market has its own variation of this flow chart.

Most shortages can be traced to a lack of raw materials or, more often, a problem at the manufacturing site. The machine breaks down. Materials are contaminated. Manufacturers are not required to disclose the reason for shortages, but recent shortages of infant formula when the drug is not available are illustrative. The FDA has required Abbott Nutrition, one of the largest suppliers of infant formula, to close its main plant because of unsanitary conditions and contaminated products.

As with infant formula shortages, it is difficult for the industry to compensate when production stops. Most of the drugs that are in short supply are generic, and usually, only a few companies make a given generic drug. If one of them has a production problem, it could mean that half or more of the expected supply is suddenly wasted.

And once supply is disrupted, it is impossible to make up the shortfall quickly. These companies rely on razor-thin margins and massive scale to operate their businesses. They have a just-in-time production schedule, meaning that the product is delivered to healthcare providers as soon as it rolls out of the factory. Don’t have warehouses with emergency stockpiles, because it wouldn’t really make financial sense for manufacturers to produce and store excess supplies.

Shortages due to distribution problems or increased demand are less common, but they do occur. Fox points to a growing strike by rail workers as a way that, even if a drug is manufactured without problems, it can cause delays in getting it to patients. And in the first weeks of the pandemic, demand for drugs including albuterol surged, creating temporary shortages.

Whatever the cause, a deficiency can have serious consequences. In 2011, there was a year-long shortage of norepinephrine, a blood pressure medication used for patients experiencing septic shock, due to production problems at three manufacturing sites. The researchers then compared the mortality rates of patients who needed norepinephrine for septic shock in a hospital that was out of the drug and relied on a substitute, versus patients treated in a hospital that still had a supply. They found that patients experiencing a lack of facilities had a higher mortality rate.

The same applies to patients who need longer treatments but can’t find the drug that will serve them best. A study found the death rate among cancer patients who had to use alternative medicine. It can be difficult for physicians to replace medications; Hospitals suffering from shortages of morphine and sedatives have reported patients being given incorrect doses of alternative drugs, leading to serious clinical problems and even death.

But if not life and death, drug shortages can meaningfully change the way patients are cared for. When I spoke to Tarantine about the Pitocin deficiency, she said that doctors can’t deliver a pregnant woman without the medication, which increases the likelihood that the patient will need a C-section delivery. C-sections are more invasive than vaginal deliveries, with a higher risk of complications and a longer recovery time. It becomes more balanced for the patient and it costs more money to provide care.

But the existence of these clinical results is not enough to force drugmakers to change their processes or start oversupplying. They are running a business, and the economics of drug production are driving this shortage. Rules won’t change unless policymakers change them.

What can the United States do to prevent future drug shortages?

The authors of the National Academies report recommended several steps the federal government could take to address drug shortages, from trade agreements that make it easier to import and export drugs in short supply to an overhaul of the national strategic stockpile, one of the few available reserves. For a small number of essential drugs if there is insufficient supply.

That list of recommendations includes more, short-term patches that would make it possible to end the deficit sooner. Hospital systems can enter into emergency purchase agreements for certain critical products, to give them another option if their main supplier has production problems. The government could also do more to secure additional supplies of some essential drugs.

Under the current system, however, it is not practical for the government to purchase an excess supply of every possible drug, nor does it make economic sense for a drug manufacturer to maintain stocks indefinitely. These solutions are really band-aids, placed when a deficiency already exists.

But how can we stop shortages from happening in the first place?

I asked Fox, one of the report’s authors, what he would prioritize if he had the chance to wave a magic wand and do a job on drug shortages. His answer: Unlocking other possible solutions starts with greater transparency.

Fox and his co-authors want pharmaceutical manufacturers to disclose more information about their manufacturing facilities and the ingredients they use to make drugs. This will help government officials identify potential weaknesses in the supply chain and better anticipate impending shortages in the event of a disruption in the supply of those materials. Beyond that, though, they’re also urging the FDA to make public its assessments of the safety and purity of drug manufacturing plants produced there.

With that information, Fox envisions creating a rating system that would let both providers and patients know more about where their drugs are coming from. This will allow them to make a more informed decision about which medicine to buy.

But high-quality drugs are more expensive to manufacture and may therefore cost more. So if hospitals still make economic decisions to prioritize cost over quality, the feds could give them a nudge, Fox said. Carrots can be tax credits for buying drugs from a high-grade manufacturer, as well as Medicaid or Medicare funding sticks for buying drugs from suppliers with a certain rating or higher condition.

You can imagine a scenario where steering buyers towards certain products can lead to greater dependence on one supplier. But Fox’s response, when I raised that point, is that many products already face that situation, given the way the pharmaceutical market is structured. At least under a system like the one he describes, manufacturers would be rewarded for taking steps that would make shortages less likely.

He said that there is no benefit for companies in investing in quality in manufacturing plants. An idea like this would be a way to change that. Target our dollars to companies that are doing well.

And even if higher-quality drugs mean more expensive drugs, Fox argued it could still be a deal. Drug shortages have already driven up costs in subtle ways: Labor costs go up as patients spend longer in hospital and require more intensive care. A substitute drug may need to be purchased, another expense. Given what we know about how deficiency can negatively affect care, the clinical benefits should be clear.

These are changes that will not happen overnight and require a serious commitment from the government. But Fox hopes the U.S. will see an opportunity, the way Covid-19 has made everyone more aware and sensitive to all kinds of supply chain issues. Getting policymakers to pay attention to drug shortages hasn’t always been easy, he said. It’s kind of a boring story. If Covid has one bright spot, it’s shining a light on these supply chain issues.

Until officials actually act, there are bound to be more shortages and more headlines like we’ve seen in the past few weeks. The problem is getting worse.

Read more: WHICH WRINKLE-REDUCING OPTION IS BEST FOR YOU?

Read more: THE USA HEALTH

Read more: SIENNA MILLER FOUND CATHARSIS IN ANATOMY OF A SCANDAL!

Read more: SCIENTISTS ARE A NEW FORCE IN THE FREELANCE REVOLUTION

For all latest news, follow The carefulu Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The carefulu Google News channel.